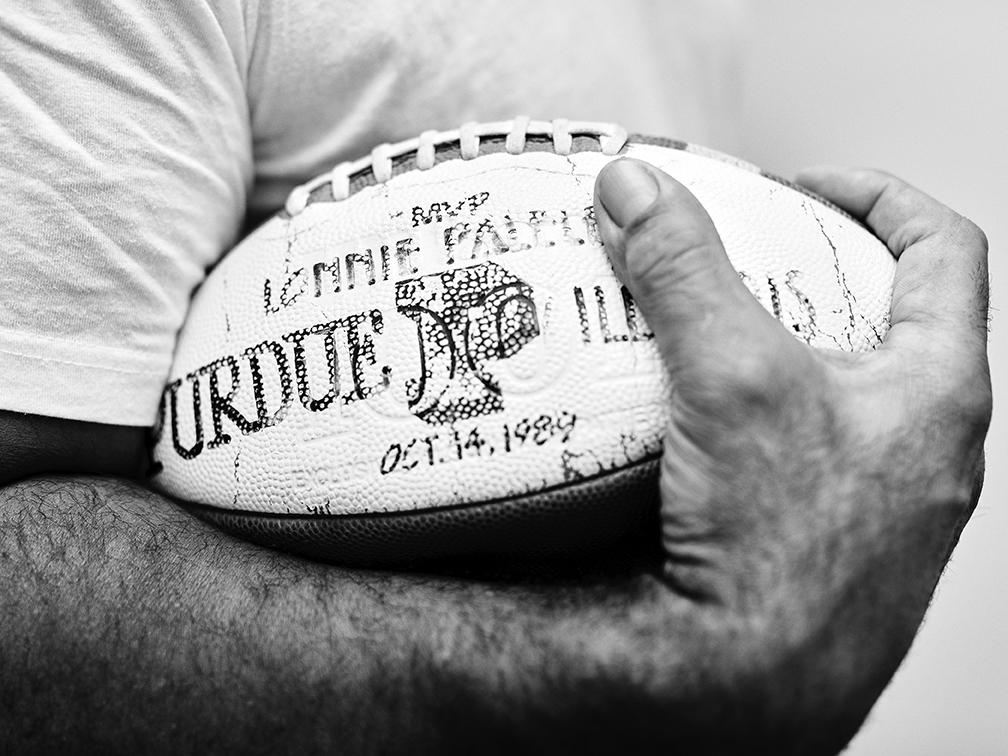

Kill Shot: How Weed Saved Lonnie Palelei

Head trauma clouded the mind and spirit of NFL lineman Lonnie Palelei. But he found a path, and a plant, that saved his life.

In a small bedroom he’d decorated with his daughter’s drawings, the man they called Big Lovely drafted a to-do list for his final 100 days. There were college teammates to visit, treasured possessions to give away, and a will to write. His affairs in order, he would finally be free to end the suffering.

Every joint hurt these days, and the noise in his head wouldn’t stop. He couldn’t sleep, he couldn’t think, and—most heartbreaking

for a man born smiling—he’d lost his will to fight.

There was so much pain, so many blurry days.

It had gotten to the point where Big Lovely could no longer

imagine a future free from pain, sorrow, and confusion.

This man loved his children more than anything on the planet. He’d coached their teams, cried at their weddings, and cheered at their college commencements. He’d cradled their

babies when the little ones woke up early, wrapping them in

his massive arms with a tenderness you wouldn’t expect from

a 6’4”, 350-pound Goliath who’d made his living smashing

heads. He loved his family so fiercely, so passionately, that he

rarely went five minutes without bragging on them.

But the time had come to say goodbye.

Father, friend, and football hero, Lonnie Palelei was finished.

Big Lovely was ready to eat a bullet.

XO

When men of extraordinary size, strength, and speed crash into each other on a football field, fans cheer, announcers swoon, and brain tissue dies. Sometimes, the trauma is grotesquely visible: a quarterback knocked silly, a woozy receiver, a linebacker stumbling back to the wrong huddle. Other times—most of the time, in fact—the damage goes unnoticed by spectator and athlete alike.

These days, the big hits trigger immediate medical evaluations designed to detect significant brain injury and prevent players from returning to the field prematurely. If dramatic symptoms are present, like loss of consciousness, amnesia, or confusion, that player’s day is done. If there’s concern but no conclusive symptoms, a team physician confiscates his helmet (he can’t sneak back in without it) and guides him to a sideline tent, where an independent neurologist tests speech, eye movement, and recall. NFL players must also pass a standardized assessment known as Maddocks’ Questions, providing info like the current month, year, quarter, and score.

These tests aren’t foolproof, but everyone agrees they’re an important, long-overdue step. That said, their value is limited to preventing additional injury. They do nothing to thwart the initial trauma.

Which, in a knockout blow, is enormous. Using high-tech mouthguards that measure the impact of a shot to the head, scientists have shown that the most violent NFL tackles can whip a player’s helmet around with 18 times the gravitational forces experienced on a roller coaster. Brain tissue is bruised, stretched, and torn, and without copious rest and recovery, critical neural functions can be permanently impaired.

But that’s not even where the worst damage is being done. Researchers now warn that the tens of thousands of smaller, “sub-concussive” hits a player sustains in a peewees-to-pro career are the most likely culprit behind a degenerative brain condition known as chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE). It’s this disease, first detected in football players by Dr. Bennet Omalu, that many physicians believe is responsible for the dementia, memory loss, suicidal thoughts, and violent outbursts experienced by hundreds, if not thousands, of ex-players.

XO

“I was a freak,” says Si’ulagi “Lonnie” Palelei. “When the college coaches came around during my senior year in high school, I was 6’4” and 260 pounds, with the athleticism of a running back. I was lifting 500 pounds, and I could run a 4.6-second 40-yard dash and jump a 36-inch vertical leap.”

These extraordinary gifts made the young two-way star—he was playing center and defensive end—a Parade All-American and one of the most coveted recruits in the class of 1988. Barry Switzer showed up from Oklahoma, and Tom Osborne flew in on his private jet to make a pitch for Nebraska. Scholarship offers poured in from major universities. Lonnie was destined for greatness.

The sudden fame was intoxicating. Just two years earlier, Lonnie had watched every last minute of his sophomore season from the sideline. He’d arrived in Blue Springs, Missouri, the summer before with zero football experience. By the end of the season, his uniform was so clean the team manager didn’t even need to launder it.

But Lonnie didn’t care. He’d grown up in an all-work, little-play family in Nu’uuli, American Samoa. It was a strong, loving family, and a fixture in the community. The Paleleis owned shops, taxis, and buses, and they prospered exporting Samoan goods to California.

As a child, Lonnie’s life was an exacting routine of work, school, and church. He’d rise before dawn to stock shelves and sweep floors, and every night seemed to bring a religious service or church function. It wasn’t all bad: Lonnie credits his parents for endowing him with a prodigious work ethic, and says their values (his father was bishop of the local Mormon stake) imbued him with a lifelong desire to serve others.

But Lonnie yearned to see America. The twelfth of 13 children, he’d watched his siblings leave the island, and he desperately wanted to follow in the footsteps of his next oldest brother, who’d earned a football scholarship to Washington State University.

At 14, Lonnie boarded an airplane for the first time, headed for Kansas City. There, in the suburban enclave of Blue Springs, he moved in with a brother 22 years his senior he’d only met twice. A veteran of the 82nd Airborne in Vietnam, TJ Palelei “was probably the meanest dude on the planet,” laughs Lonnie. “He didn’t smoke, drink, or do drugs, and he kept me on a tighter leash than any other kid in school.”

But Lonnie knew how to follow rules, and he was happier than he’d ever been. He’d made it to America, and he was learning to play football.

XOOX

Lonnie’s dream died midway through the fourth game of his freshman season at Purdue University.

He should’ve been playing for a powerhouse school like Nebraska or Oklahoma, but Purdue coach Fred Akers had sent emissaries to Blue Springs with an offer Lonnie couldn’t resist. “I didn’t even know where Purdue was,” laughs Lonnie, “but I’d never seen that kind of cash, either. We had eight Parade All-Americans in the incoming class. It was the best team money could buy.”

If power corrupts, so does stardom, especially when heaped on the shoulders of a naïve 18-year-old. Lonnie’s success as a high-school junior had turned his life into a values-warping circus. “Overnight, people around Blue Springs were like, ‘Here, take whatever you want.’ This one man had a convertible ’67 Camaro. One day he tells me, ‘Hey, come pick up my daughter, take my car.’ It was so crazy. I went from being the weird brown kid hearing racist [taunts] to being absolutely loved.”

What teenager wouldn’t take advantage? Lonnie took the money, drove the Camaro, skipped classes, slept with the girls—quite a few of them—and made the starting lineup at Purdue. He was invincible, and everything was going to plan: Agents were already soliciting him for early entry to the NFL draft.

Then he got a clean line to Notre Dame’s quarterback on a third down—and in an instant his career earning potential took what one analyst estimated was a $80 million hit.

“When I came around the guard, it’s looking like one of those plays a defensive end dreams about,” recalls Lonnie. “I grab the quarterback high, and I’m about to slam him to the ground when the other defensive end gets him by the waist. As he tackles the guy, his legs whip around and hit mine.”

The force demolished Lonnie’s left knee. Dislocated it, tore all four ligaments to shreds. His hamstring sheared off the bone behind his knee and rolled up into his butt. His quadricep ripped in two places, and his calf muscle exploded, balling up so tight down around his Achilles that doctors had to fish it back up with a hook.

“My lower leg was sticking out sideways, perpendicular to my femur,” says Lonnie. “I never doubted I’d play again, but I knew right then that I’d never get to rush the passer. In three seconds, I went from the happiest moment of my life to the saddest. From then on, I’d always be playing against the guy with my dream job.”

When Lonnie returned for his sophomore year, the Purdue coaches made him an interior lineman. It was a miracle he could even run, but he’d lost the speed and agility that made him a freak. His best shot now was joining the nameless, faceless ranks of guards and tackles who bang heads for the superstars who bang supermodels. Lonnie’s future was in the trenches.

XX

Imagine a bowl of Jell-O, all jiggly and soft and squishy. Now imagine three pounds of that Jell-O bouncing around inside your skull after your car T-bones a wall at 30 mph. If you’re a lineman, your jiggly-soft three-pound brain will hit that wall as many as 10 times in a single game, according to one study. If you manage to play a full 16-game season, that’s 160 minor car accidents—not counting the pre-season and playoffs.

Amazingly, your brain doesn’t disintegrate at 30 mph, and you probably won’t lose consciousness. The squishiness helps; it creates an elasticity that helps absorb the impact. But the back-and-forth bouncing caused by an NFL hit overloads your evolutionary resilience; deep inside, brain matter stretched this violently suffers tiny tears and ruptures. Without proper rest and recovery, those ruptures don’t heal, creating clusters of dead tissue and encouraging the build-up of an abnormal protein called tau that clogs neural pathways.

Those 10 hits—and the 50 other “dings” an average lineman racks up each game—are the type Dr. Omalu, the pioneering brain specialist portrayed by Will Smith in the movie Concussion, is most worried about. They are the sub-concussive traumas that players don’t report. And why would you? You’re competitive by nature, and from the first time you pulled on pads, you’ve been taught to “man up” and ignore the pain. Later on, team docs administer really sweet drugs, and coaches challenge you to play through injury. So you do, knowing the average NFL career only lasts three years. With a rookie always itching to take your place, your paycheck, and your glory, another ding isn’t worth mentioning.

Over time, those hits add up, and your brain tissue degenerates. And by then it’s too late. The symptoms of cognitive decline—memory loss, confusion, impaired judgment, impulse control problems, aggression, depression, suicidality, parkinsonism, and dementia—don’t appear until permanent damage is done.

Doctors at leading research institutions like Boston University’s CTE Center are working to develop advanced diagnostic testing, but for now the only certain detection method is a post-mortem examination of a victim’s brain. Hundreds of players have signed up to donate their brains, and for good reason: A September 2019 report in the Annals of Neurology showed that 86% of the 266 deceased players tested by the CTE Center showed signs of the disease. Further, the study’s authors estimate that the risk of developing CTE increases 30% a year during a player’s lifetime. For those who enjoy a long pro career, the risk curve becomes a hockey stick. After 15 years in the trenches, a lineman like Lonnie is 10 times as likely to develop CTE as young men who stop playing after high school or college.

OXO

Lonnie suffered at least three knockout blows during his playing career, including a college hit so fierce he got up and careened towards the opposing team’s sideline before being redirected by teammates. He returned for the next series, not missing a play after this or any of his other concussions.

But those big hits were just the exclamation points. Linemen bang helmets on almost every running play, enduring those silent sub-concussive shocks with a “shake-it-off” mentality. By the midpoint of his seven-year NFL career, Lonnie’s brain was so sensitive that he would have blurred vision or feel dizzy after every ding—literally dozens of times a game. On Mondays, he would have to watch game film to remember the details.

Lonnie also spent time as a wedge buster on kickoffs, perhaps the most dangerous position in the sport. “They’d tell us, ‘Run down and take out as many guys as you can. We’ll wake you up and bring you to the sideline.’ We were the expendable second-teamers, and everyone was going for the kill shot. But sometimes you’d put your helmet right in a guy’s grill, and the kill shot would knock you out.”

Drugs kept Lonnie and his teammates on the field. Painkillers were handed out like Halloween candy, and every Saturday night team doctors would “line us up and inject us with Toradol [a powerful anti-inflammatory]. By game time, we’d feel wonderful. Nothing hurt at all. That would last until Tuesday morning, and then you’d wake up and want to fucking kill yourself. You’d feel all the old injuries, plus all the new ones. It took an hour to get out of bed.”

His body is riddled with scars, long white welts that bear witness to a litany of injuries suffered while playing in Pittsburgh, Cleveland, New York, Baltimore, and Philadelphia. He’s had surgery on both knees, both shoulders, an elbow, an ankle, and a hand. Several fingers are permanently crooked from dislocations, and a detached tendon in his right thumb makes it hard to hold a fork. His right elbow has bone spurs that keep him from fully extending his arm, and both shoulders have limited range of motion. Walking has gotten easier with a stretching routine, but the stiffness is ever-present. Walking behind him is like watching a double amputee learn to use new prosthetics; one peg-legged limp offsets but doesn’t quite balance the other.

By the time Lonnie joined the Eagles, the last stop in his NFL career, the injuries were taking a toll on more than his body. “I always tried to be a good husband and father,” he says, “but I was losing whole days [in an opioid fog], and the concussions were affecting my personality. I was moody and forgetful and impatient, and my behavior was getting more and more erratic and irresponsible. It was like I’d become a different person, and my family was paying the price.”

XXXO

The day after Lonnie’s catastrophic knee injury, and three days after his 18th birthday, his first daughter was born back in Missouri. Her mother had been a casual acquaintance, what you’d now call a friend with benefits. They’d fooled around before he left for Purdue, and she entered her senior year at Blue Springs High School with a bulging belly.

Prior to the Notre Dame game, “doing the right thing” looked easy. They’d get married, she’d finish high school, and they’d spend a year in Purdue’s married student housing before Lonnie landed a top-10 NFL contract. He hated to miss out on the college fun, but he came from strong family and was determined to face up to his responsibilities.

Hobbling into the maternity ward on one leg, the other encased in a full-length cast, the right thing no longer looked so easy. For the first time in his life, Lonnie was scared. The freak from Blue Springs who would cash in on his athleticism was history, and he didn’t have the grades to finish college without football. (He would later discover that he suffered from severe dyslexia, which he’d masked with the help of “tutors” who wrote his papers.)

It’s no cliché to say that moments like these take the measure of a man. In Lonnie’s case, the Palelei work ethic kicked in hard. His dream may have died, but he still had a passion for the game and knew the NFL trenches would pay better than any blue-collar job. He hit the weight room with a vengeance, pushing his knee relentlessly. He rehabbed day and night through the off-season and surprised his teammates by starting his sophomore season.

Two years later, after transferring to the University of Nevada-Las Vegas for his junior and senior years, he was drafted in the fifth round by the Pittsburgh Steelers. He’d made it, and his young family was growing: His wife, now 20, had given birth to a son, the second of four they would have together.

OOXO

“When I retired from the NFL, they gave me a pat on the back and a big bag of Vicodin,” says Lonnie. That’s when the spiral started in earnest, the pills kicking off a stretch of hazy years punctuated by professional successes and personal failures—and by troubling brain-injury symptoms.

He’d hung up his cleats despite multiple contract offers and against the wishes of his agent. After seven seasons, the joy was gone, and he’d fallen in love with a new hobby: long-distance motorcycling. Aboard his Honda Gold Wing, some camping gear lashed to his seat, he felt an incredible sense of freedom. There were no mandatory workouts, no film sessions, just an open road and the camaraderie of fellow, like-minded wanderers he met in places like the Badlands and Yosemite and the desert Southwest.

He rode the country like a man sprung from jail, but the adventures increasingly became a means to escape a troubled home life. The concussions, injuries, insomnia, and painkillers had created a vicious cycle. Unable to exercise, his digestive system wracked by opioids, he gained weight—at one point cresting 400 pounds, 80 heavier than his playing days. The added weight aggravated his knee, back, and ankle pain, further reducing mobility and limiting his sleep to fitful bursts of two and three hours. The lack of sleep in turn intensified what was going on in his head: migraines, memory loss, depression, and inexplicable bursts of anger.

“Little things were sending me into a rage,” he recalls. “A guy’s grocery cart would accidentally bump mine, and I’d want to put my fist through his face.”

Lonnie never raised a hand to his children, who say they were deeply loved and largely shielded from the darker aspects of his illness. But he would pick fights with strangers at bars, and he behaved poorly towards his first wife. There were minor frictions that evolved into bitter arguments, then infidelity and ultimately a big fight that led to their divorce. When he tells the story, his broad shoulders shrink with shame, and tears roll down his cheeks. The fight started over something small, he recalls, then escalated into a shouting match and physical altercation that spilled out into the neighborhood.

He’s nervous speaking about this incident in a national magazine, where his mother and newer friends will see it. But he hopes his transparency will help others struggling with the chaos of brain injury. “I’m ashamed of the way I acted, and I would never excuse what happened. That was me—I did those things. But it also wasn’t me.” He was behaving in ways he didn’t understand and couldn’t control.

Lonnie’s problems didn’t attract much attention if any; to most observers, he was enjoying a successful post-NFL career. He held a series of satisfying jobs in Las Vegas, coached his kids’ teams, and played the part of popular UNLV alum around town. He led a local high school to several state football championships, and he mentored dozens of athletes, many of them young Samoans in a broad network he maintains. He directed operations for the city’s Meals on Wheels program as a manager at the diocese’s Catholic Charities foundation. And he volunteered at the homeless shelter his sister ran.

But the roller coaster from fugue to fury and back was driving him into a deep darkness. Entire days and weeks disappeared, he wasn’t fully present for his kids, and he feared the burden he’d become if he let it get much worse. A man who once steamrolled 250-pound linebackers felt powerless to stop the suffering.

Which is how Lonnie Palelei came to write his 100-day plan.

XO

Lonnie rolled his first joint at 11. His older brothers thought it’d be funny to teach him, and eventually they allowed him a hit or two. He partied some in high school and college, and more frequently in the NFL off-season as his aches and pains intensified. To this day, his mother doesn’t know about his marijuana use, and he always feels a bit guilty lighting up. “As observant Mormons,” he says, “we were taught to see it as a drug, not a medicine.”

With this story, though, she’s going to find out. And that will have to be okay, because Lonnie credits cannabis with saving his life, and he’s willing to risk his mother’s disapproval if his story can help others.

His turning point—when he decided not to eat a bullet, after all—came when he found counseling and fine-tuned his cannabis intake. For years, he’d hit a bong to take the edge off his pain. But then he started hearing about patients using medical marijuana for depression, insomnia, and other ailments, and he decided to try a serious experiment. He’d sample different strains, concentrations, and smoking patterns. In football terms, it was a Hail Mary from midfield with :02 on the clock. But what did he have to lose?

With the help of a couple of private growers—Good Samaritan/mad scientist types—he honed in on several strains that provided more than just pain relief. These buds relaxed him in a way he hadn’t experienced before, and he started to sleep soundly for the first time in years. Another discovery: He felt better when he evened out his consumption—by smoking less, but more often. He claims that a steady-state THC saturation helps him control symptoms more effectively, something I witnessed first-hand. Every three hours or so during our interview, he would visibly tire, lose his train of thought, and start grasping for words. We’d break for a “session” and 15 minutes later he’d be back with renewed energy and coherence. (Lonnie smokes a bong and consumes an eighth of an ounce a day. Some of it is store-bought, and some is a secret strain. He won’t share the specifics, because he’s not comfortable with the idea that someone may copy him in lieu of doing their own research.)

The vicious cycle unwound bit by bit as his friends tinkered with their formulas. With better rest came less agony in his knees and shoulders. With less agony came more exercise—and fewer pills. Weight loss followed—he’s down to 325 pounds—as did a clearer mind and better short-term recall. Gradually, he weaned himself from painkillers and alcohol, and his moods stopped swinging so wildly.

He started taking CBD gummies, and he says they help him focus. For the first time in his life, he’s enjoying literature. “Before, people would talk about a great book they were reading, and I’d think, ‘Dang, I’m never gonna read that.’ But now I can concentrate long enough, and that’s opening up a whole new world to me. Now there’s this broader spectrum on which I can connect with people.”

His biggest breakthrough was limonene. One of the 100 or so terpenes present in cannabis, it’s a fragrant chemical that’s also found in many plants and trees. It’s best known as the active component in the oils of citrus peels, and it’s long been used as a naturopathic remedy, fragrance, and degreasing solvent.

Among cannabis researchers, limonene is regarded as a promising treatment for lung cancer, anxiety, and depression. Far too little research exists to substantiate any anecdotal claims, but Lonnie swears that limonene has dramatically reduced his “stinkin’ thinking.” Trying herb with higher and higher percentages of the terpene, he found that he was feeling happier—and more like his true self.

Which is how Lonnie Palelei came to scrap his 100-day plan.

XOXOO

In less than a year on Facebook, Lonnie has accumulated almost as many friends as I’ve made in 10. It’s easy to see why: In person and online, he exudes infectious energy, exuberantly bear-hugging new acquaintances and “hearting” every comment on his wall. His football brotherhood runs deep, too; his day is peppered with calls and emails from old teammates eager to see him or share a laugh.

The man who could barely make it through a day before dialing in his cannabis regimen is starting to realize how much fun he can have in his second act as a big-hearted, wisdom-dispensing, love-making, pot-smoking, motorcycle-riding grandpa.

He’s also making up for lost time with his family. He shuttles between the East Coast and Southern California, where his daughters and grandchildren live, and Las Vegas, home to his mother and older sister. In between, he tries to catch his sons when they have leave; he speaks glowingly of their honors and awards as graduates of the Naval Academy and West Point.

Lonnie has finally found a bit of peace—albeit one leavened with a poignant urgency. Alternately excited and wistful, he rattles off plans for the future but knows the concussions will someday finish him off. That’s why he wants to get his story out. “I want my life, the good parts and the bad parts, to make a difference,” he tells me. “And I want people to know that this herb that has been villainized for so long is truly a healing plant.”

Before agreeing to an interview, Lonnie had called each of his children and asked their permission. All four heartily approved, to hell with any stigma. And so he opens up, with disarming grace and courage, about a life alternately broken and resilient. Towards the end of our two days together, we sit beneath a palm tree a stone’s throw from the Pacific Ocean, and he shares a mantra from, of all places, the movie Groundhog Day. “What Bill Murray finally learns in that movie,” he reminds me, “is that we’ve just got to work on perfecting today, right now. In the end, that’s all that really matters—what you did today to make the people around you feel a little bit better.”

OX

Weed saved Lonnie, at least for now, and we’re lucky for that. It eased the agony of his many injuries. It let him sleep, at long last, which helped in so many ways. It smoothed out his moods and metabolism. And it provided clarity, the kind he needed to realize a bullet would destroy the brain he wanted to donate to CTE researchers.

Weed also let in some light. Credit the limonene or the CBD or the saturation protocol. But give credit. For the first time in years, dark clouds didn’t fill Lonnie’s sky.

Today, his knees and shoulders and fingers and feet still hurt, and the concussion symptoms will never really go away. But in that small bedroom where he drafted his 100-day plan, Lonnie is now plotting a road trip around America, and he wants to pitch the NFL on hiring him to speak to other players about cannabis. Lonnie’s clock is ticking, he knows that, but he has purpose again, and he has hope.

Down the hallway, laughter erupts and Lonnie’s face lights up. Those projects—and our interview—can wait. Big Lovely has two little grandchildren, and he loves them more than anything on the planet.